Quantifying the Far Future Effects of Interventions

Part of a series on quantitative models for cause selection.

Introduction

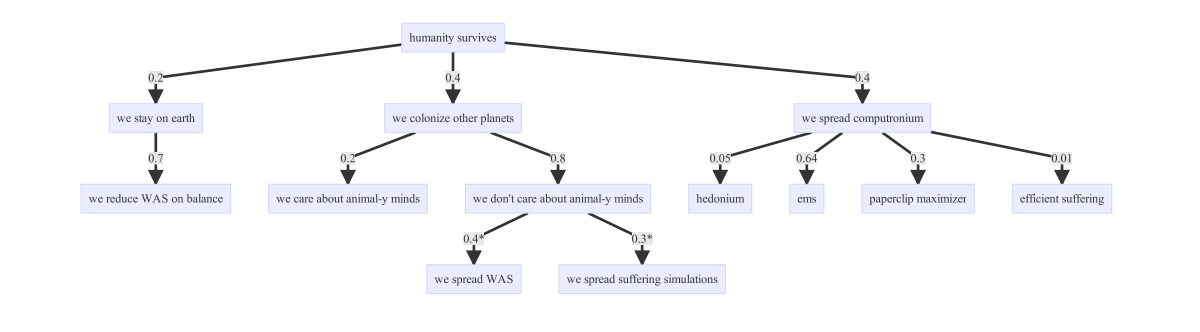

In the past I’ve written qualitatively about what sorts of interventions likely have the best far-future effects. But qualitative analysis is maybe not the best way to decide this sort of thing, so let’s build some quantitative models.

I have constructed a model of various interventions and put them in a spreadsheet. This essay describes how I came up with the formulas to estimate the value of each intervention and makes a rough attempt at estimating the inputs to the formulas. For each input, I give either a mean and σ1 or an 80% confidence interval (which can be converted into a mean and σ). Then I combine them to get a mean and σ for the estimated value of the intervention.

This essay acts as a supplement to my explanation of my quantitative model. The other post explains how the model works; this one goes into the nitty-gritty details of why I set up the inputs the way I did.

Note: All the confidence intervals here are rough first attempts and don’t represent my current best estimates; my main goal is to explain how I developed the presented series of models. I use dozens of different confidence intervals in this essay, so for the sake of time I have not revised them as I changed them. To see my up-to-date estimates, see my final model. I’m happy to hear things you think I should change, and I’ll edit my final model to incorporate feedback. And if you want to change the numbers, you can download the spreadsheet and mess around with it. This describes how to use the spreadsheet.

Continue reading